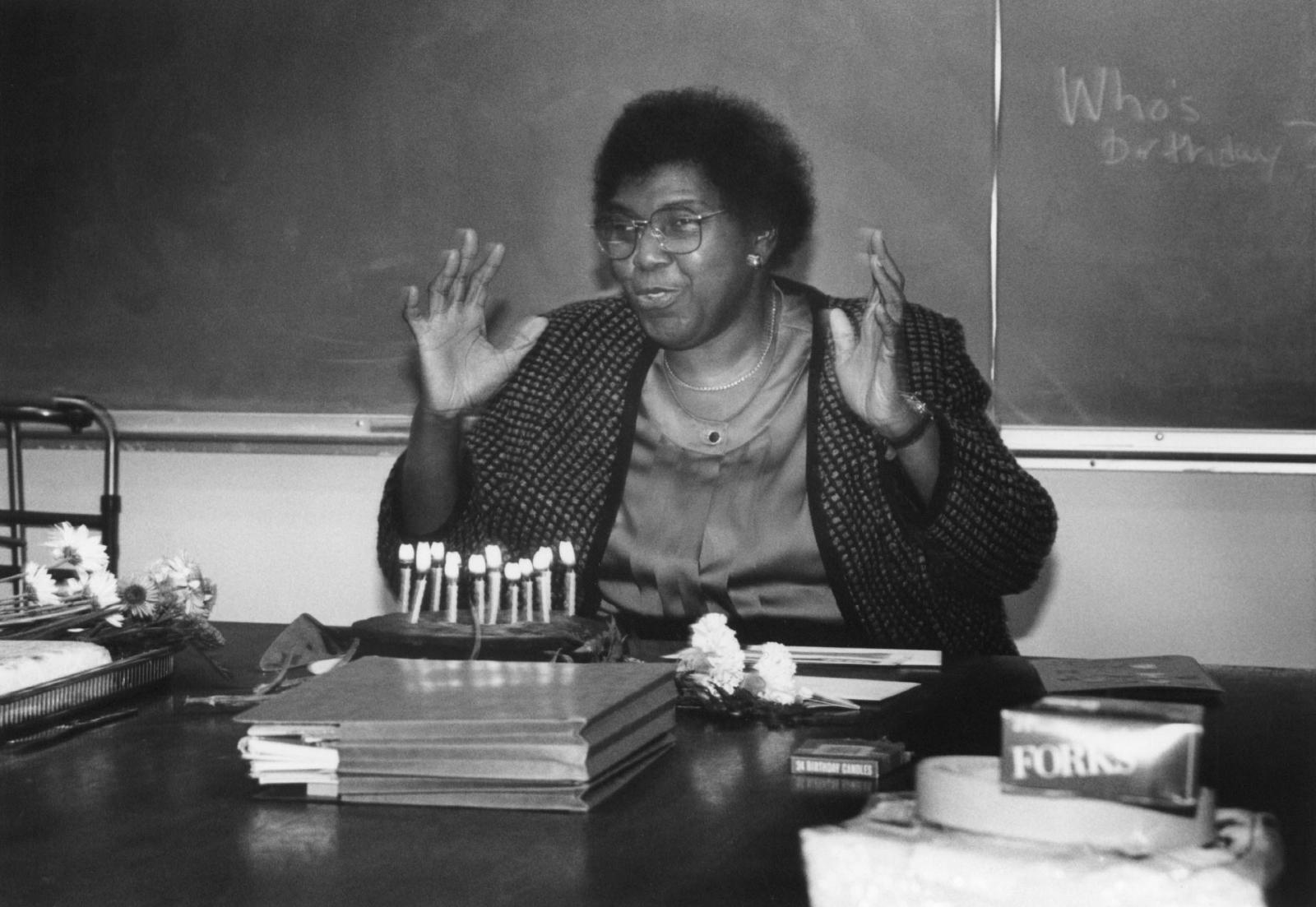

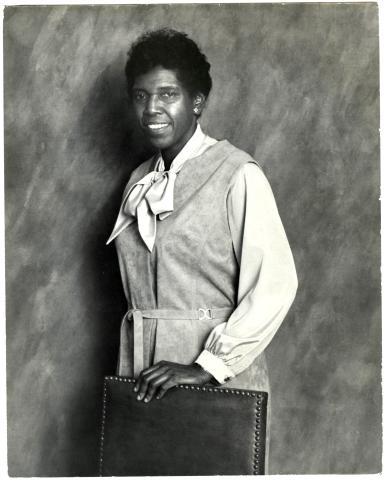

Educator, policymaker and civic rights leader

Barbara Jordan Statue Unveiling

A student-initiated effort results in the installation of a statue of Barbara Jordan, the first female public figure honored on the university campus in its 126-year history.

A woman of firsts

The first Black woman ever elected to Congress from the South

The first Black woman in America to preside over a legislative body

The first Black chief executive in the nation

The first woman and the first Black keynote speaker at a Democratic National Convention

Lasting impact at LBJ: Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values

The Barbara Jordan Visiting Professorship is funded through the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values,

an endowment created in 1997 intended to promote training in ethics and values-based decision making.

Current Chair: Professor Peniel Joseph

Center for the Study of Race and Democracy (CSRD)

Peniel Joseph holds a joint professorship appointment at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and the History Department in the College of Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin. He is also the founding director of the LBJ School's Center for the Study of Race and Democracy (CSRD).

His career focus has been on "Black Power Studies," which encompasses interdisciplinary fields such as Africana studies, law and society, women's and ethnic studies, and political science.

Prior Chair: Former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin

The Biography of Barbara Jordan, Courtesy of the U.S. House of Representatives

(1936-1996)

From her seat on the House Judiciary Committee, Barbara Jordan of Texas—the first Black woman ever elected to Congress from the South—expertly interpreted the issues of the Watergate impeachment investigation at a time when many Americans despaired about the Constitution and the country.

Jordan was one of the first Black lawmakers elected from the South since 1898, and during her three terms in office, her pragmatic leadership style enabled her to build broad coalitions of support in her diverse district. “I am willing to work through any structure,” she said. “I am not so hard that I cannot bend as long as my basic principles are intact.”

Barbara Charline Jordan was born in Houston, Texas, on February 21, 1936, one of three daughters of Benjamin M. Jordan and Arlyne Patten Jordan. Barbara Jordan was educated in the Houston public schools and graduated from Phillis Wheatley High School in 1952. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Texas Southern University in 1956 and a law degree from Boston University in 1959. That same year, she was admitted to the Massachusetts and Texas bars, and she began to practice law in Houston in 1960.

In 1960, Jordan, in addition to beginning her legal career, worked on John F. Kennedy’s Democratic presidential campaign. She eventually helped manage a highly organized get-out-the-vote program that served Houston’s 40 African-American precincts. In 1962 and 1964, Jordan ran for the Texas house of representatives but lost both times. In 1966, she ran for the Texas senate when court-enforced redistricting created a constituency that consisted largely of minority voters. Jordan won, becoming the first Black state senator in Texas since 1883 and the first Black woman elected to the Texas state legislature. Jordan received a cool welcome from the other 30 White and male senators. Undeterred, Jordan quickly established herself as an effective legislator who pushed through bills establishing the state’s first minimum wage law, antidiscrimination clauses in business contracts, and the Texas fair employment practices commission.

On March 28, 1972, Jordan was elected president pro tempore of the Texas senate, making her the first Black woman in America to preside over a legislative body. One of Jordan’s responsibilities as president pro tempore was to serve as acting governor when the governor and lieutenant governor were out of the state. When Jordan filled that largely ceremonial role on June 10, 1972, she became the first Black chief executive in the nation.

In 1971, Jordan entered the race for the Texas congressional seat encompassing downtown Houston. Jordan took the primary with 80 percent of the vote. In the general election, against Republican Paul Merritt, she won 81 percent of the vote. Along with Andrew Young of Georgia, Jordan became the first African American in the twentieth century elected to Congress from the Deep South. In the next two campaign cycles, Jordan overwhelmed her opposition, capturing 85 percent of the total vote in both general elections. In both her Texas legislative career and in the U.S. House, Jordan pursued influence and change within existing systems. “I sought the power points,” she once said. “I knew if I were going to get anything done, [the congressional and party leaders] would be the ones to help me get it done.” Immediately upon arriving in Congress, Jordan worked to establish relationships with the rest of the Texas delegation, which wielded outsized influence in the House. In the House, Jordan sought out powerful committee assignments, where, as a Black woman, she could blaze new trails and magnify her influence. She disregarded suggestions that she accept a seat on the Education and Labor Committee and instead used her connection with former President Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas—she had once been his guest at the White House during her time as a state legislator—to intercede on her behalf with Wilbur Daigh Mills of Arkansas, who, as chair of the Ways and Means Committee, also led the Democratic Committee on Committees. With Johnson’s help, Jordan landed a seat on the Judiciary Committee, where she served for her three terms in the House. In the 94th and 95th Congresses (1975–1979), she was also assigned to the Committee on Government Operations.

In the summer of 1974, as the Judiciary Committee considered articles of impeachment against President Nixon for crimes associated with the Watergate scandal, Jordan delivered opening remarks that shook the committee room and captivated the large television audience that had tuned in to the proceedings.

“My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total,” Jordan said.

“I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” After explaining why she supported each of the five articles of impeachment against President Nixon, Jordan concluded by saying that if the Judiciary Committee did not find the evidence compelling enough, “then perhaps the eighteenth-century Constitution should be abandoned to a twentieth-century paper shredder.” Reaction to Jordan’s statement was overwhelming. Jordan recalled that people swarmed around her car after the hearings to congratulate her, and many people sent the Texas Representative letters of praise.

Back home in Houston, a new billboard read: “Thank you, Barbara Jordan, for explaining the Constitution to us.”

During her career, Jordan sought legislative remedies to expand the reach of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. “The momentum of the 1960’s has run out,” Jordan declared. “Congress will be called upon to defend progress already made rather than undertake new initiatives.

In 1975, a decade after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, Jordan supported legislation to extend the act’s provisions for an additional 10 years, noting that state and local officials had continued to implement policies aimed at suppressing voters of color. “The barriers continue,” Jordan said. “And so must the Voting Rights Act—the most effective statute minorities have to guarantee that one day those barriers will come down.” She introduced legislation to extend the act’s voter protections to language minorities, particularly Hispanic Americans. Under her bill, states and local jurisdictions in which more than 5 percent of the population spoke a single language other than English would be subject to Voting Rights Act’s special provisions if officials only printed election materials in English. The bill also required areas covered by the Voting Rights Act to seek approval from federal authorities before implementing changes to their voting procedures. Her legislation was incorporated into the Voting Rights Act’s 1975 re-authorization.

In 1976, Jordan became the first woman and the first Black keynote speaker at a Democratic National Convention.

Appearing after a subdued speech by Ohio Senator John Herschel Glenn Jr., Jordan energized the convention with her soaring oratory. “We are a people in search of a national community,” she told the delegates, “attempting to fulfill our national purpose, to create and sustain a society in which all of us are equal. . . . We cannot improve on the system of government, handed down to us by the founders of the Republic, but we can find new ways to implement that system and to realize our destiny.” Amid celebration of the national bicentennial, and in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and Watergate, Jordan’s message of hope and resilience, like her commanding voice, resonated with Americans. She campaigned widely for Democratic presidential candidate James Earl “Jimmy” Carter, who defeated President Ford in the general election. Though it was widely speculated that Carter was considering Jordan for Attorney General, he offered her the job as ambassador to the United Nations. Jordan did not accept the offer, explaining that she would only accept a position “consistent with my background.”

In 1978, Jordan was appointed the Lyndon Johnson Chair in National Policy at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas in Austin, where she taught until the early 1990s. She continued to lecture widely on national affairs.

Jordan died in Austin, Texas, on January 17, 1996, from pneumonia that was a complication of leukemia. Newspapers across the country published extensive obituaries that celebrated her oratory, her defense of the Constitution, and the role she played in inspiring generations of minority women in politics. “She left Congress after only three terms, a mere six years,” the editors of the New York Times wrote. “No landmark legislation bears her name."

Yet few lawmakers in this century have left a more profound and positive impression on the nation than Barbara Jordan.”